The Parable of the Weeds among the Wheat

- Fr. Terry Miller

- Jul 11, 2023

- 9 min read

Matthew 13:24-30, 36-43

He put another parable before them, saying, “The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a man who sowed good seed in his field, but while his men were sleeping, his enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat and went away. So when the plants came up and bore grain, then the weeds appeared also. And the servants of the master of the house came and said to him, ‘Master, did you not sow good seed in your field? How then does it have weeds?’ He said to them, ‘An enemy has done this.’ So the servants said to him, ‘Then do you want us to go and gather them?’ But he said, ‘No, lest in gathering the weeds you root up the wheat along with them. Let both grow together until the harvest, and at harvest time I will tell the reapers, “Gather the weeds first and bind them in bundles to be burned, but gather the wheat into my barn.”’

Then Jesus left the crowds and went into the house. And his disciples came to him, saying, “Explain to us the parable of the weeds of the field.” He answered, “The one who sows the good seed is the Son of Man. The field is the world, and the good seed is the sons of the kingdom. The weeds are the sons of the evil one, and the enemy who sowed them is the devil. The harvest is the end of the age, and the reapers are angels. Just as the weeds are gathered and burned with fire, so will it be at the end of the age. The Son of Man will send his angels, and they will gather out of his kingdom all causes of sin and all law-breakers, and throw them into the fiery furnace. In that place there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father. He who has ears, let him hear.

Reflection

Over the centuries, the Parable of the Weeds Among the Wheat has often been cited in support of various degrees of religious toleration. The wheat and the weeds are identified by Jesus as referring to reborn followers of Christ (“sons of the kingdom”) and the “weeds” as “sons of the evil one.” Yet Jesus does not explicitly define who belongs in either group (beyond calling them “the righteous” and the “lawbreakers,” respectively). And so it is inevitable that subsequent interpreters would draw their own conclusions based in their theological commitments, their cultural contexts, and, yes, their prejudices. To point this out does not however mean that this has been a wholly illegitimate distortion of the parable or that it is spawned from malicious intent. For, once the wheat is identified with orthodox believers and the weeds with heretics, the command. “Let both grow together until the harvest” becomes a call for toleration.

To go back to the early days of the church, the Church Father St. John Chrysostom declared in a sermon that “it is not right to put a heretic to death, since an implacable war would be brought into the world” which would lead to the death of many saints. Furthermore, he suggested that the phrase “lest in gathering the weeds you root up the wheat along with them” can mean "that of the very tares [weeds] it is likely that many may change and become wheat." However, not to make Chrysostom out to be an early proponent of civil liberties, he also asserted that God does not forbid depriving heretics of their freedom of speech, and “breaking up their assemblies and confederacies.”

In his "Letter to Bishop Roger of Chalons," Wazo (985-1048AD), the Bishop of Liége in Germany, displayed a nuanced approach to cases of heresy that was not common in his day. In arguing for religious tolerance, he relied on the parable to argue that "the church should let dissent grow with orthodoxy until the Lord comes to separate and judge them".

Centuries later, in the midst of the heated battles of the Reformation, both the Protestant leaders John Calvin (1509-64) and Theodore Beza (1519-1605) and their opponents, the Counter-Reformers (who appealed to St Thomas Aquinas and the Medieval Inquisitors), opposed toleration, but did so in ways that sought to harmonize the killing of heretics with the parable. Some argued that a number of weeds can actually be uprooted without harming the wheat. Others argued that the weeds in the parable could be identified with moral offenders within the church, not heretics per se. Consequently, since the parable did not refer to heretics, it was perfectly permissible persecute them. Alternatively the prohibition against pulling up the weeds could be applied only to the clergy, not to the political leaders. Another approach was put forward by Thomas Müntzer (1489–1525) who called for rooting up the tares, claiming that the time of harvest had come. (This is a perfect example of the kind of nitpicking and qualifying of the Law that Jesus railed against in his ministry.)

In contrast to Calvin and Beza, though, Martin Luther preached a sermon in 1525 on the parable in which he affirmed that only God can separate false from true believers and noted that killing heretics or unbelievers ends any opportunity they may have for salvation:

From this observe what raging and furious people we have been these many years, in that we desired to force others to believe; the Turks with the sword, heretics with fire, the Jews with death, and thus outroot the tares by our own power, as if we were the ones who could reign over hearts and spirits, and make them pious and right, which God's Word alone must do. But by murder we separate the people from the Word, so that it cannot possibly work upon them and we bring thus, with one stroke a double murder upon ourselves, as far as it lies in our power, namely, in that we murder the body for time and the soul for eternity, and afterwards say we did God a service by our actions, and wish to merit something special in heaven.

He concluded that "although the weeds hinder the wheat, yet they make it the more beautiful to behold.” Several years later, however, Luther changed his mind on the subject. Luther emphasized then that the magistrates should eliminate heretics: "The magistrate bears the sword with the command to cut off offense. ... Now the most dangerous and atrocious offense is false teaching and an incorrect church service.”

The parable also featured, again on the side of not executing heretics, in the Anabaptist theologian Balthasar Hubmaier’s On Heretics and Those who Burn Them, published in 1624. (Great title, isn’t it?) Hubmaier contended that heretics should be “overcome with holy knowledge, not angrily but softly.” He believed that it was right for the secular power to execute criminals, but that, as heretics could not injure body or soul—true Christians having the power of the word of God to defend them—they presented an opportunity for good to come out of evil.

Similarly, Roger Williams, a Baptist theologian and founder of Rhode Island, used this parable to support government toleration of all of the "weeds" (heretics) in the world, because civil persecution often inadvertently hurts the "wheat" (believers) too. Instead, Williams believed it was God's duty to judge in the end, not man's. This parable lent further support to Williams' biblical philosophy of a wall of separation between church and state as described in his 1644 book, The Bloody Tenent of Persecution.

Meanwhile, back in England, the writer John Milton, in his Areopagitica (1644), called for freedom of speech and condemned Parliament's attempt to license printing, referring to this parable and the Parable of Dragnet, both found in Matthew 13: “it is not possible for man to sever the wheat from the tares, the good fish from the other fry; that must be the Angels' ministry at the end of mortal things.”

But voices urging toleration were not those that prevailed—certainly not for many centuries. Indeed, it was not until the American Revolution, with the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791, that religious tolerance came to be generally affirmed.

As citizens of a nation that does hold to the right of religious freedom, what does this parable have to say to us? Would it be possible for Christians to use the powers of government to persecute heretics? If so, would that be desirable? If not, then are we to affirmed secularists’ calls for ethical and religious pluralism? Or is Jesus just speaking to individuals, the “wheat” and the “weeds,” within the church? What does it mean to be “religiously tolerant,” or “tolerantly religious” anyway? More, fundamentally, What is the “good” that is sought in religious tolerance? These questions are certainly worth pondering as faithful Christians.

Artistic Illumination

1. SONG:

“Come, Ye Thankful People, Come” | Performed by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir | Words and music by Henry Alford. Alfred used the parable as the primary basis for this harvest hymn.

“Mixed like weeds in wheatfields” | Words and music by Carl P. Daw Jr

“Tho' in the outward church below” by John Newton (of “Amazing Grace” fame) | Sung to the tune, Old Hundredth (which we are familiar with as “Praise God From Whom All Blessings Flow”)

2. ART

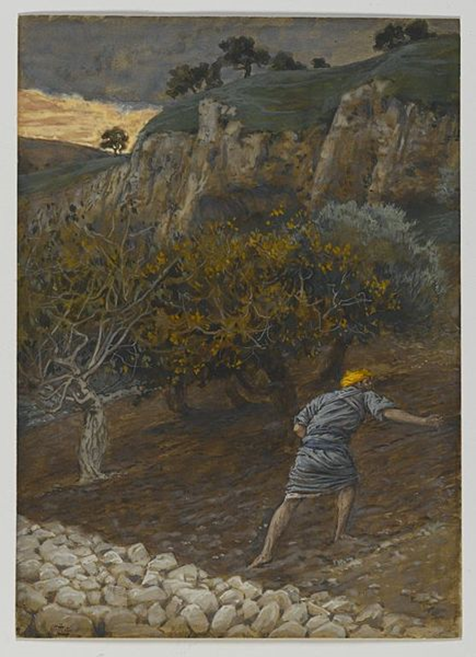

The farmer sleeps while the winged devil in the distant field sows his weeds.

Scholars believe that the weeds or tares mentioned in this passage were probably darnel, a common and pernicious weed that infested wheat fields. Up until seed maturity, it looks very much like wheat. The problem is that darnel is intoxicating, and in a big enough dose, it can kill a person. Farmers thus would have to take care to separate it out from their true harvest—unless they were planning to add darnel to beer or bread on purpose, in order to get high. (See here for more about darnel) In this painting, as well as many others, the human subjects are to be a sleep at midday, suggesting that the farmhands were intoxicated, possibly by darnel-infused beer. Consequently, the question of the means by which the darnel came to be sown in the wheat field is mute—it was already there! What then does this say about the origins of evil? Yet, even as evils may already be present, even now the devil may be adding more, as is indicated by the figure in the background.

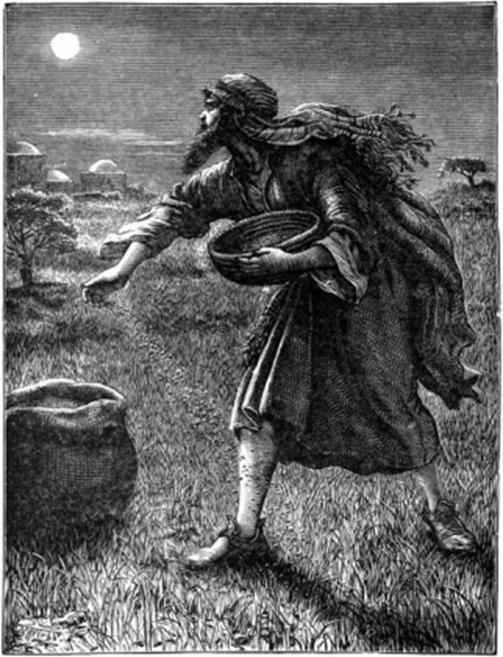

It took Millais seven years to design twenty images inspired by New Testament parables for the Dalziel Brothers, and the resulting prints are considered pinnacles of wood engraved illustration. The artist wrote to his publishers, "I can do ordinary drawings as quickly as most men, but these designs can scarcely be regarded in the same light—each Parable I illustrate perhaps a dozen times before I fix [the image]." After completing a design, Millais transferred it to a woodblock coated with "Chinese" white for skilled engravers to carve. Finally, he reviewed proofs, and final adjustments were made before the final printing. Millais's detailed naturalism and down-to-earth imagery combined to produce a work distinctly different than most religious art of the period.

In Rops’ drawing, the “enemy” is explicitly named as Satan and is depicted as a giant death-like character, “sowing” human “seeds” into a late Victorian city-scape (presumably Paris). The point seems to be to suggest that the evils/evil persons commonly found in the 19th century industrial metropolis of northern Europe in the 19th century (think Charles Dickens).

As indicated above, almost all of the artwork created depicting the Parable of the Wheat and Weeds focuses on the enemy sowing weeds. Notable exceptions are this 1992 triptych by Dinah Roe Kendall and Scott Freeman’s “The Parable of the Weeds Among the Wheat,” which appears to depict Jesus sowing wheat.

The following are a few pieces focus on the harvest/judgment:

Eugène Burnand (Swiss, 1850-1921) illustrated “The Parable of the Tares” with three drawings, two of which focus on burning the weeds.

Here the Master has the field hands burning the tares after the wheat has been harvested.

Comments