Jacob Wrestles with the Angel

- Fr. Terry Miller

- Aug 15, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 4

Genesis 32

22 The same night he arose and took his two wives, his two female servants, and his eleven children, and crossed the ford of the Jabbok. 23 He took them and sent them across the stream, and everything else that he had. 24 And Jacob was left alone. And a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day. 25 When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he touched his hip socket, and Jacob's hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. 26 Then he said, “Let me go, for the day has broken.” But Jacob said, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.” 27 And he said to him, “What is your name?” And he said, “Jacob” (“supplanter”). 28 Then he said, “Your name shall no longer be called Jacob, but Israel (“strives with God”), for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.” 29 Then Jacob asked him, “Please tell me your name.” But he said, “Why is it that you ask my name?” And there he blessed him. 30 So Jacob called the name of the place Peniel (“face of God”), saying, “For I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered.” 31 The sun rose upon him as he passed Peniel, limping because of his hip. 32 Therefore to this day the people of Israel do not eat the sinew of the thigh that is on the hip socket, because he touched the socket of Jacob's hip on the sinew of the thigh.

Artistic Illumination

Medieval depictions of Jacob wrestling with the Angel, limited almost exclusively to miniatures in illuminated Bibles, have been straightforward, showing a man dressed in Medieval clothing wrestling with an angel, dressed in white robe and shown with wings on the back, what has become the conventional portrayal of an angel in Western art.

Fashion Sidenote: Penuel is not only the name Jacob gives the area, but is also a kind of clothing (in which the angel appeared) from which the French peignoir originated. Peignoir is usually made of muslin, chiffon, silk or other transparent material, an analogue of a men's dressing gown. Often trimmed with lace. In many paintings by medieval painters, the angel is depicted in something resembling a peignoir dress.

Likewise, the few examples of the story in Renaissance art carry on this conventional depiction, even as the pose of the opponents becomes more dynamic.

With the emergence of Dutch hegemony in the 1600s, artistic portrayals of the Biblical story diverge along two paths. The first path, taken by landscape painters, has the drama of the divine-human contest diminished, reduced to a negligible part of a larger backdrop, namely, the landscape. While one assumes this was done for practical reasons, in order to exhibit the artist’s skill in portraying the natural environment, the visual diminishment reminds us of how this event, and all of the events of the Bible, are often considered by those outside as being of little significance, as being unworthy of even a footnote in the history of human civilization. But to the Jews, and Christians who follow after them, the encounters of Abraham and Jacob and Moses and others with God are of much greater significance and consequence than, say, the building of the pyramids in Egypt or the rise of the Roman Empire or the development of the nuclear bomb, or any of the other events that are the subject of world history.

The other path, taken largely by Italian artists, continued the pattern of dramatizing the contest between Jacob and the angel, using vivid colors and angular poses to emphasize the tension of the scene.

Rembrandt captures the moment when the angel, seeing that he was not overpowering Jacob, "touched the structure of his thigh." But the angel does not at all look defeated. In fact, of the two, only Jacob is making efforts, the angel is calm and serene, he seems to embrace Jacob, and does not measure strength with him. This is not a fight of wrestlers, but a meeting full of special significance.

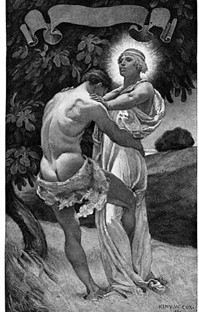

In the 1800s, this subject was taken up by popular illustrators of the Bible, whose etchings, woodcuts and prints continued the conventional man-vs.-angel theme with little advancement in the interpretation of the subject.

At the same time, several impressionist artists took up the subject for their revolutionary artistic stylings. Some well-known Impressionists, like Gauguin and Delacroix, offered interpretations of Jacob’s wrestling with angels, but other lesser-known artists also took up the story, using techniques reminiscent of more-celebrated artists.

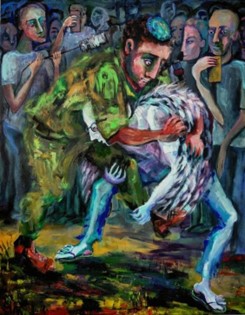

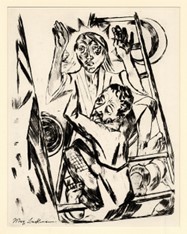

In the 1900s depictions of Jacob wrestling with the angel take on a darker tone, becoming harder, muddier, heavier, “scratchier.” This shift to the rough and gloomy follows the emergence of Jews as artists in their own right and as the situation of Jews in Europe became more perilous in the first half of the 20th century. In this way, the struggle of Israel-the-person mirrored the struggle of Israel-the-people.

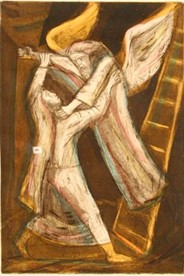

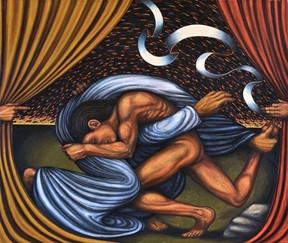

One of the interesting developments in the artistic depiction of the story of Jacob and the angel is the trend in the late 20th century towards depicting the struggle horizontally, with both Jacob and the angel pushing against or past each other, not away as when the angel wishes to exit. One could only speculate as to the meaning of this shift—the struggle is clearly this worldly, yet the nature of Jacob’s partner is ambiguous—is the Stranger divine or human?

Jewish artist Sussman portrays this episode as a whirl of wings and arms, flailing, flapping, legs planted and upturned. The focal point is the face of Jacob, clearly struggling but still holding on tightly. Above his head is an orb of light, signifying the break of day, by which Jacob will be able to see his opponent’s face for the first time. This painting doesn’t capture just one moment in the narrative but many moments superimposed on one another. However, amid all the motion, Jacob’s face remains fixed in an expression that seems to indicate that he is almost at the point of surrender. I imagine that this particular freeze frame captures the moment at which God pronounces his blessing on Jacob, right after he has given him the new name ‘Israel’ – ‘he who strives with God.’ Jacob is looking upward and inward as he realizes that validation, blessing and victory come from God alone, not from earthly fathers and definitely not from his own cunning.

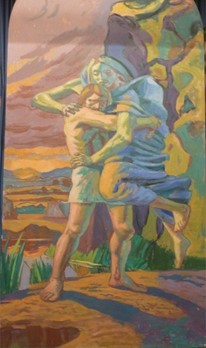

Like most artists before him, Edward Knippers, an Anglican in northern Virginia, has interpreted in his first two depictions of Jacob’s opponent (1990, 1998) as a massive and solidly muscled figure, whose impressive frame stands out dramatically against the twilight sky. This is no ethereal divine presence engaged in a wrestling match with Jacob, but a corporeal force to be reckoned with, who grapples with Jacob, skin on skin. You can almost feel the heat of exertion radiating from their bodies in the cool of the night. Through this painting, Knippers expresses his belief in an embodied divinity – a God active and present in the physical world. His angel looks fully human – if it weren’t for the title of the painting, we might assume this image was simply of two wrestling men. The figures’ nakedness too strips away any sense of time or place, allowing them to transcend the specific location of the biblical tradition to take on a more universal significance.

As Knippers himself insists, “The human body is at the center of my artistic imagination because the body is an essential element in the Christian doctrines of Creation, Incarnation, and Resurrection. Disembodiment is not an option for the Christian.” In his later two paintings of the scene (2008 and 2012 above), the same very physical angel is shrouded in fractured, cubist colors, suggesting something more than a natural human opponent. Together these four pieces present the ambiguity of the encounter—both the earthiness of the conflict and its spiritual dimension.

Comments